by Maya Bell

AS IRMA INFANTE ENTERED THE BIG, WHITE TENT FESTOONED WITH orange and green balloons, she thought she had been invited to celebrate a new research grant for Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, perhaps one that would give other pancreatic cancer patients hope of surviving the usually fatal disease. But when she spotted former University of Miami President Donna E. Shalala, who is now a U.S. congresswoman, among the many dignitaries inside, Infante knew “something really big” was up. Like many of those gathered in the tent, Infante was soon on her feet, cheering University President Julio Frenk and Sylvester Director Stephen D. Nimer’s historic announcement this past July that Sylvester’s excellence in clinical care, research, and outreach to its diverse community had just earned the institution the National Cancer Institute’s prestigious NCI designation.

Nearly 50 years after it began as Florida’s first Cancer Control Research Program and just seven years since Shalala recruited Nimer to drive Sylvester’s quest for NCI designation, the renowned leukemia and lymphoma specialist had achieved that goal: Sylvester is now one of just 71 cancer centers in the nation and only the second in the state to meet the rigorous NCI-designation standards for groundbreaking research focused on developing new and better approaches to preventing, diagnosing, and treating cancer.

“This is a milestone not just for Sylvester and the University of Miami, but also for the people of South Florida and throughout the state, the nation, the hemisphere, and the world,” Frenk told the applauding crowd in the tent on the Miller School of Medicine’s Schoninger Research Quadrangle.

This recognition shows everybody what I already knew—that Sylvester is the best of the best.

This recognition shows everybody what I already knew—that Sylvester is the best of the best.

Taking the microphone, Nimer added, “We have worked tirelessly to become one of the nation’s great cancer centers. Now we have confirmation from the NCI that we are one of the great cancer centers in the United States.”

But as Nimer made clear, there is no rest ahead for the 300 “extraordinarily accomplished, collaborative, driven, and hard- working scientists, administrators, and educators who focused on achieving this milestone,” nor for the 15 key leaders whose 1,300-page application ensured that Sylvester was evaluated, in part, for being uniquely positioned to ask the research questions today that cancer centers in an increasingly diverse nation, and world, will need to answer in the future.

“This is just the beginning,” Nimer said. “The best is yet to come.”

Robert Croyle, director of the NCI’s Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, noted that the NCI had recently “raised the bar” for becoming what he called one of the “crown jewels in the nation’s war on cancer” by requiring NCI centers to engage their communities in addressing the local cancer burden—an area where he said Sylvester “really set the pace.”

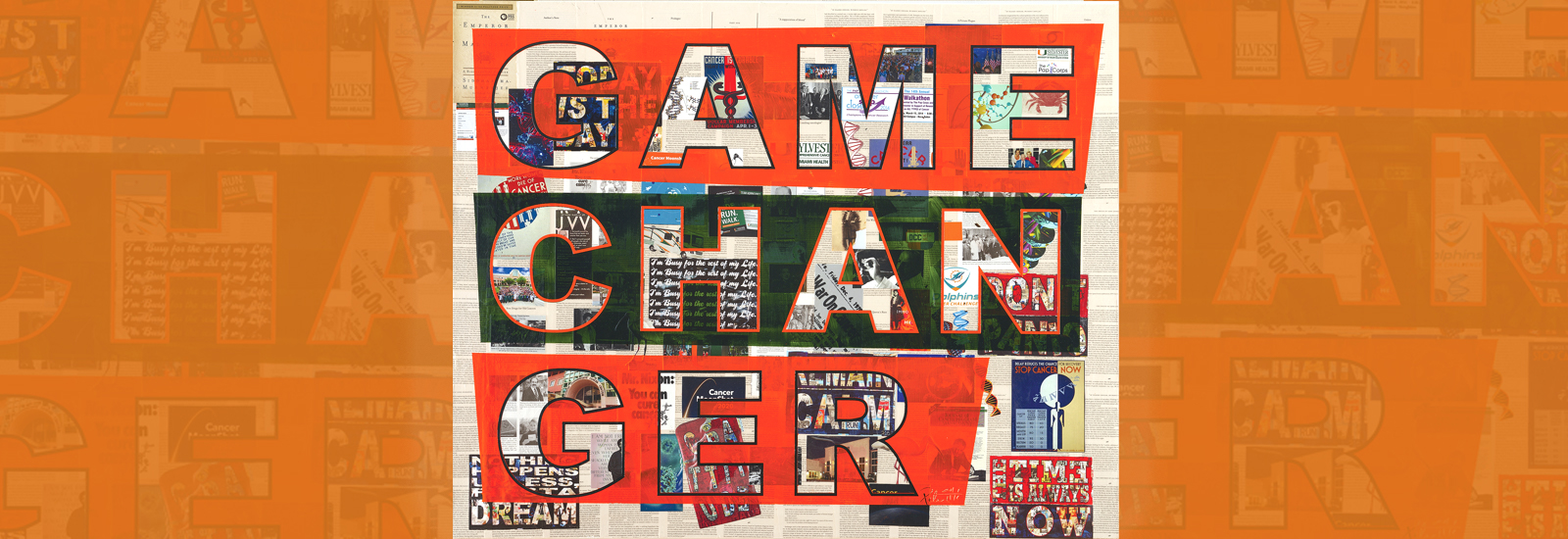

Sylvester’s Firefighter Cancer Initiative and its Game Changer outreach vehicle were among the public health programs that helped notch its NCI designation 33 years after philanthropist Harcourt Sylvester Jr. pledged $27.5 million to benefit the medical school’s then 13-year-old cancer center. The first to document the excess burden of cancer among Florida firefighters, Sylvester researchers began developing methods to reduce their cancer risk five years ago. Wrapped in original artwork by acclaimed Miami artist Peter Tunney, the Game Changer vehicle travels across South Florida, bringing cancer screenings and health information to underserved communities.

Though a layperson, Infante understood the significance of the designation almost as much as any of the oncologists, hematologists, surgeons, researchers, and administrators gathered under the tent.

She understood that all the balloons, the speeches, the applause, and the congratulatory hugs were really for patients like her—patients whose lives are suddenly upended by a cancer diagnosis, patients whose hopes for a future will now be brighter because they can access novel cancer treatments and cutting-edge clinical trials available only at the NCI-designated center right in their back yard.

What’s more, Sylvester researchers will have access to more federal funds to accelerate Sylvester’s most critical work: discovering lifesaving cancer breakthroughs for South Florida’s diverse community.

Infante’s life depended on all three when last summer, she visited a gastroenterologist for what she assumed was a persistent bout of indigestion. But a battery of tests confirmed she had pancreatic cancer, a silent killer that often claims its victims within months of detection.

The first oncologist Infante saw offered no hope. He told her the tumor was inoperable and summoned a priest. Infante, who came to the U.S. from Cuba on the 1980 Mariel boatlift as a teenager, spent the next few days, the bleakest of her life, praying to Cuba’s patron saint, Our Lady of Charity. Then she turned to the Miller School of Medicine, where she had worked as an administrative assistant and data manager for 16 years, for a second opinion.

Almost immediately, Alan Livingstone, a surgical oncologist at Sylvester, confirmed her tumor was inoperable and, worse, that it had spread. “But he grabbed me by the shoulders, and said, ‘Irma, you are young. You are strong. You can fight this,” the 54-year-old mother of three sons recalls. “In the darkest storm, he was my light.”

This recognition shows everybody what I already knew—that Sylvester is the best of the best.

This recognition shows everybody what I already knew—that Sylvester is the best of the best.