FINDING THEIR FOOTING

Working in two groups—a floor plan team and a longitudinal sections team—the students spent six long, hot days in the Snoa, measuring and sketching. Though the space lacks air conditioning, Caribbean breezes blow through dozens of louvered windows crowned by blue half-moon stained-glass insets that splash the interior with a cool cobalt-colored glow.

A symbol of Jewish resilience in the face of relentless persecution, the sound-dampening sand is variously said to honor the Spanish Jews who muffled their footsteps when praying in secret during the Inquisition, or to evoke the desert terrain through which Moses wandered after leading his people out of slavery in Egypt.

It did not, however, make things easy for the students who were responsible for establishing a datum line, the vertical reference point that anchors all architectural drawings. “In a place where the floor is sand,” explains Hernández, B.Arch. ’80, “the datum line is even more important, because the floor is so irregular.”

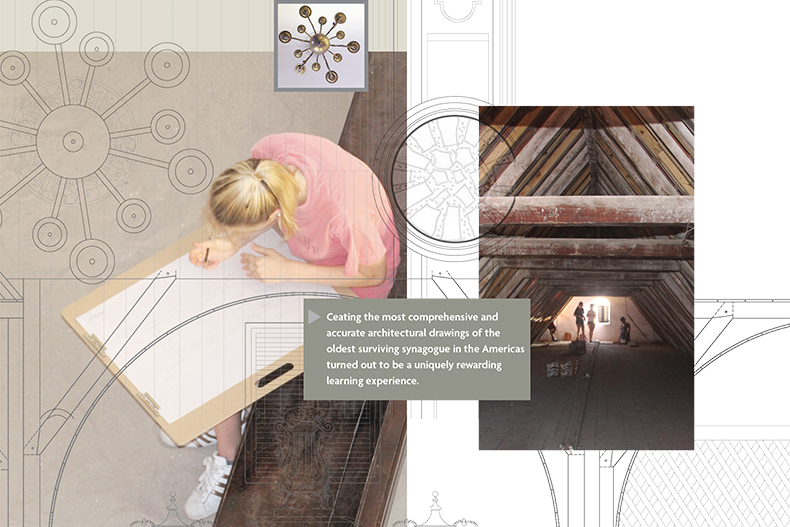

Ricardo Lopez, B.Arch. ’00, M.A.S.T. ’07, assistant director of the School of Architecture’s Center for Urban and Community Design, teaches a class on standards for surveying historic American buildings. In Curaçao, he guided students in the use of lasers, levels, plumb lines, tape measures, string, and even a translucent, flexible tube filled with water to set the perfect datum line.

“In ancient times,” says Lopez, “they probably used a piece of an animal intestine to do the same thing.”

A triumphant yell punctuated Mikvé Israel-Emanuel’s hushed tranquility when the students finally established the datum line, painstakingly marked with dots on masking tape about five feet above the shifting sands on both floors.

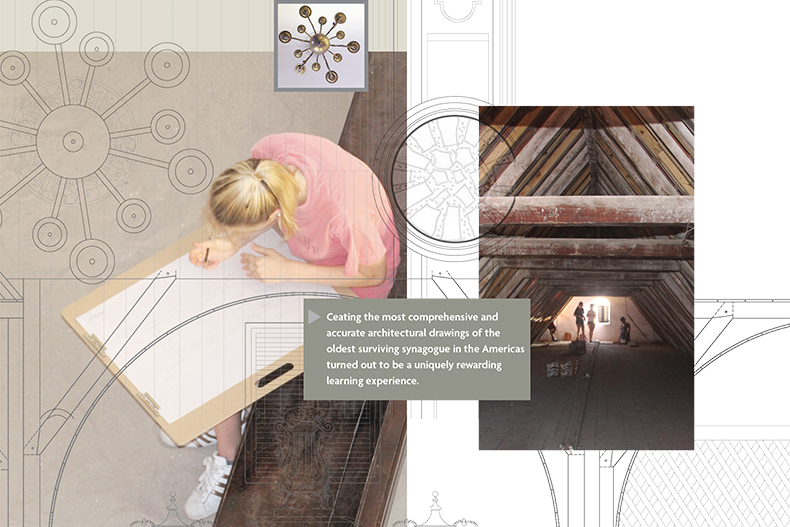

Outside, a drone operated by the Center for Computational Science’s Chris Mader, director of software engineering, and Amin Sarafraz, a computer vision expert, took thousands of photos of the building’s north wall. The images were then melded into the bird’s-eye views that architects have used since antiquity to convey their plans.

While the concepts of architectural drafting have barely changed over the centuries, says Hernández, who directs the School of Architecture’s historic preservation certificate program, the pencil “keeps changing. The drone is like another pencil—it just so happens it’s a very fast pencil.”

WISDOM PRESERVED

Back on campus, students refined and combined the dozens of individual drawings they made of the synagogue’s lofty interior spaces, as well as many of its intricate details and monumental furnishings: the ark on the bimah that holds 18 precious torahs, the reading platform where the spiritual leader conducts services, the towering brass candle chandeliers, the majestic columns, the Dutch gables and semi-circular vaulted ceilings, the impressive 19th-century organ, and the latticework of timbers forming the attics.

During the second part of the semester, the students proposed additions to the auxiliary spaces in the Snoa’s courtyard that, perhaps, would draw more people to the historic treasure while honoring its rich heritage.

“There is a wisdom embedded in a culture’s built environment that goes back generations,” Hernández says. “The structures are like textbooks. We can learn from them and adapt them for contemporary use.”

For the students, the unique learning experience offered by their intimate interaction with the synagogue and its history was deeply moving. “I lost track of time,” recalls student Hector Valdivia Arreta. “The air was different, and I’m not only talking about the dust. You could feel the energy of the place and the intentions of the design. When the work was tedious, you could rest your mind in a place filled with inspiration—simply by lying down on the sand floor and looking up.”