“It was a serendipitous discovery,” recalls McNeer, a professor of clinical at the Miller School of Medicine. “Suction has been used to remove everything from stomach contents to blood. But this is perhaps the first time it’s been considered for use in suctioning out aerosols.”

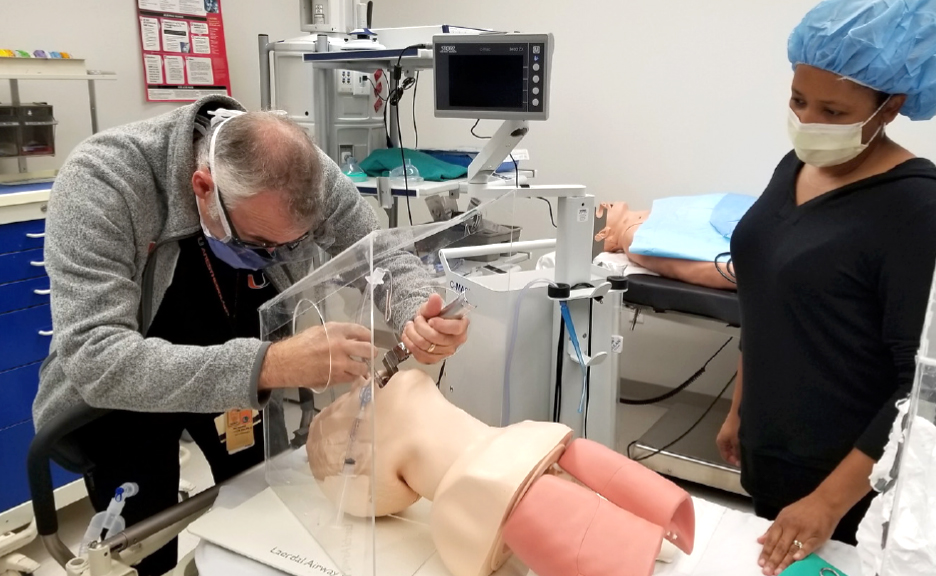

Used in tandem, the tube and intubation box are an added layer of protection for health care providers, McNeer said.

The intubation box itself is made of acrylic and covers a patient’s head. It has two circular ports through which an anesthesiologist inserts his gloved hands and arms to perform an airway procedure. “We knew that anesthesiologists were at risk of being exposed to splatter and respiratory droplets when performing intubations, so we were trying to find a way to protect them,” says Suresh Atapattu, B.S.B.E. ’96, M.S.B.E. ’01, a biomedical engineer at the Miller School’s International Medicine Institute, who designed the box. He found inspiration for its design from half a world away—a physician in Taiwan who had constructed and used a clear barrier device to protect health care workers when intubating COVID-19 patients.

Atapattu designed and constructed his own iteration of the box. Once the prototype had been perfected, Maxwell Jarosz, architect and manager of the fabrication lab and model shop at the School of Architecture, built others, donating them to medical facilities in South Florida. Some are now being used at Ryder Trauma Center, where McNeer performs airway procedures on patients who are brought in with serious and often life-threatening injuries.

and often life-threatening injuries. As for the suction tube, Jarosz is working with McNeer on a design that is more ergonomically friendly than the Yankauer that was initially used. Once the design is finalized, the tubes will be 3D-printed in mass quantities at the School of Architecture.

THE PANDEMIC BEHIND BARS

Kathryn Nowotny, an assistant professor in the University of Miami’s Department of Sociology, together with public health scientis ts from two other institutions, launched the COVID Prison Project to encourage policies and procedures that better protect one of the most vulnerable but most neglected populations.

The group tracks the pandemic’s impact on the roughly 2.7 million people who are incarcerated and

the more than 423,000 employees in state and federal prisons and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers across the nation and in Puerto Rico.

In addition to the altruistic argument for her research, Nowotny cites the radiating impact of the spread of the virus on incarcerated people.

“These are people’s parents, spouses, children, brothers, and sisters, or friends,” she says. “And correctional officers and other staff come in and out regularly and go home to their communities.”

A cadre of students from the three collaborating universities manually collect and update the data by visiting every state’s and the federal government’s prison websites daily. A $20,000 Langeloth Foundation grant will help to automate and expand the operation—to include data from the thousands of county jails across the nation.

“We want prison officials to see what other states might be doing to improve conditions,” says Nowotny. “And for them to say: ‘Maybe we should be doing it, too.’ ”

THE POWER OF ART