Jon Baldessari, executive director of housing operations and facilities, joined the University in the early 1990s when new notions about residential college systems were emerging nationally.

“We became much more student-centered and holistic in our understanding of education and began focusing on all the things we look at today that help students persist so they can nail their career choice and be successful,” Baldessari says.

Both leaders concur that the need for new housing became increasingly urgent. Most campus buildings, built in the post-World War II era of the 1950s and 1960s, were requiring more money and attention to maintain dated mechanical systems, and University Village, opened in 2006, was the last residential construction completed. The idea to replace student housing had been explored for years, Smart says, but hadn’t risen to priority status. By 2012—with more students wanting to live on campus, new data demonstrating the impact of housing on student success, and changes pending in University leadership—there was impetus for action.

Smart worked closely with Patricia A. Whitely, Ed.D. ’94, vice president for student affairs, to develop the report submitted that year recommending an assessment of campus buildings.

Whitely, who has served in her role since 1997, has held a range of positions that put her closely in touch with students. Her ear is tuned to hear what students want from their college experience.

“Our focus as a university is on our students,” Whitely says, noting that in 2012 “one of the things we had to do before tackling housing for first-year students was to build housing for sophomores, juniors, and seniors.”

The proposal to build something was a small first step. Ascertaining the national standard, deciding on the design to fit the master plan, and determining the complexities of a housing project for the 21st century—all within budget—was a leap into the unknown. Many voices—faculty, students, and parents, as well as staff in facilities and real estate divisions—expressed opinions of what to do.

“It’s been collectively hundreds, thousands of inputs into this process of being able to create a housing system that we are confident supports student education as well as student development into the 21st century,” Smart says. The team went through several iterations of design, and the final plan was selected from a design competition—a decision majorly influenced by the opening of the Shalala Student Center.

“That changed the campus,” Smart says. “We’d always talked about the lake as being the heart of the campus, and with the construction of the new center and renovations at the Whitten Center, it was becoming a hub of activity the way we’d imagined,” he adds.

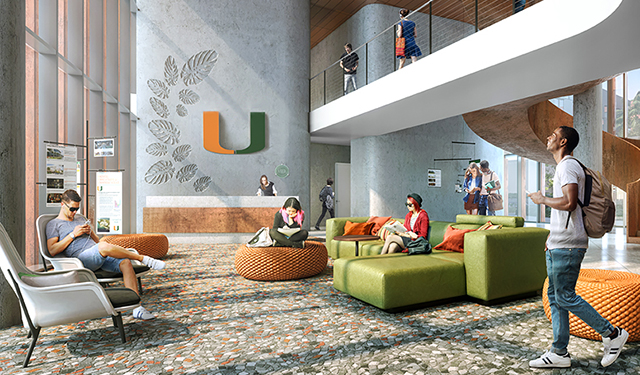

The shimmering glass-and-pillars structure on the north side of the lake had a rippling effect. “When architecture is done well, it adds values in ways that you wouldn’t anticipate. We wanted to bring that same sense of energy to the south side of the lake,” says Smart.

Jessica Brumley, vice president for facilities operations and planning, joined the University in early 2018 and inherited the reins of the project.

“It’s been a fabulous opportunity professionally to jump into a project of this magnitude, one with such a visible, identifiable presence, together with Pat Whitely and her team,” says Brumley.

“So many parties—project managers, financial staff, central staff, and others—had to come together behind the scenes to make this possible,” she states. “This project puts a stake in the ground for the University’s future. The Braman Miller Center for Jewish Life and the Toppel Career Center have broadened our presence on Ponce. This project, with its depth and volume, serves to say: ‘We’re here—and we’re making a statement.’ ”