She would quickly learn, however, that these women and others like them that DHS and local law enforcement agencies subsequently brought to her for treatment presented a whole new set of health care challenges beyond the scope of anything her team had in place. “It was not just a matter of performing a simple GYN exam,” Potter recalls. “They had experienced trauma, and they had tremendous medical care and mental health needs.” Some of the women had suffered broken bones that never healed properly, and, in a few cases, some had been branded with tattoos by their pimps to show ownership.

Even the simplest of tasks were a challenge for them. “They couldn’t sit in a waiting room,” Potter says. “I would sit next to them, and I could see the anxiety start to mount because there were too many people. And, they had been brainwashed into thinking the traffickers were going to come looking for them. And, if not the traffickers, people who were working for the traffickers.”

Potter had already assembled a cadre of providers—nurse practitioners, physicians, and psychologists—who were all willing to help. But what was needed most, she knew, was a dedicated space just for the survivors. So, she called the county’s top prosecutor, Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle, B.Ed. ’73.

“She advocated on our behalf,” Potter says of Fernandez Rundle’s efforts. “She made it clear that there was a gap in health care access for these patients and that they desperately needed specialized, traumainformed health care services.”

Shortly thereafter, the Trafficking Healthcare Resources and Intra-Disciplinary Victim Services and Education clinic, or THRIVE, was born.

A collaboration between the Miller School of Medicine and Jackson Health System, the clinic, which Potter, its inaugural director, describes as “a onestop shop” for human trafficking victims, provides everything from primary and gynecological care to psychiatric and behavioral health services under one roof. DHS, the Human Trafficking Unit of the Miami-Dade County State Attorney’s Office, and other anti-human trafficking organizations refer victims to the clinic. But what makes this model one of the first of its kind is the way it administers health care, starting with the way patients are brought in.

There is no waiting area—patients are admitted and discharged inside the examination room. “This isn’t the way medicine usually operates,” says Panagiota Caralis, B.S. ’71, M.D. ’75, a professor of medicine at the Miller School and medical director for THRIVE. “You never have a registration, an exam, and a discharge in one place. But it’s been done that way in recognition of the sensitivities of these patients.”

While most of the patients need care from multiple specialists, THRIVE never requires them to navigate a maze of medical facilities. The providers come to them. And, to avoid re-traumatizing patients, their medical histories are taken only once. “Survivors often cannot remember or do not want to remember,” says Potter. “Their stories change over time. They aren’t lying. They have blocked out the trauma to survive."

Mental health care is their most critical need, with many of them showing all the classic symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder—flashbacks, nightmares, depression, and suicide attempts.

“We can’t just say, ‘OK, I’m going to treat your hypertension and send you on your merry way,’ ” says Caralis, who is also medical director for women veterans health at the Miami Veterans Administration. “The mental health piece is key to having them come back into the community as productive people who are able to function on their own and not fall back because there is no other choice. It’s going to take role models and peers to help them make it. And we’re looking at a program to try and do that.”

Each referral, and successful treatment, is a victory of gargantuan proportions for the THRIVE team, as they have painfully come to realize that even getting survivors to walk through the clinic’s door hinges on law enforcement’s ability to rescue and persuade victims to cooperate. And accomplishing that task, says Fernandez Rundle, can be exceedingly difficult, as many victims are unwilling to cooperate for fear of retaliation at the hands of their traffickers.

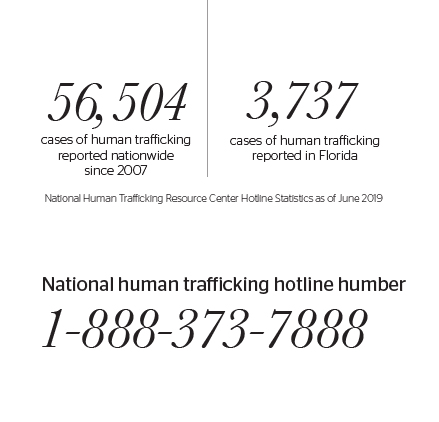

Much like Potter was once unaware of the serious health consequences trafficking victims face, Fernandez Rundle’s office found itself at a similar disadvantage eight years ago after learning that Florida ranked No. 2 in the nation for human trafficking cases, with Miami one of the primary hotspots.

“So, we set out to learn and understand what it actually was, who and where the victims were, and where in Miami-Dade the predators were,” notes Fernandez Rundle.

Her office established a human trafficking unit and a task force made up of police officers from multiple agencies. Soon, their caseload of human trafficking related cases mushroomed, going from only three in 2012 to more than 600 today.

Fernandez Rundle calls the partnership with THRIVE invaluable, saying the clinic has helped victims heal and become strong enough “to break the emotional chains of their enslavement and be an effective part of a criminal prosecution.”

THRIVE physicians, nurses, and social workers, explains Potter, have been able to break those emotional chains by building trust with the victims, employing patient navigators—usually survivors themselves who have reentered the workforce—to chaperone new survivors through each clinical visit.

One of those patient navigators is Shanika Ampah, a mother of nine.

Sexually abused as a child, Ampah ran away from home at the age of 11 and fell victim to a criminal enterprise that generates global profits of $150 billion a year—nearly $100 billion of which comes from commercial sexual exploitation.

“When I was being trafficked, it wasn’t a 9-to-5 situation,” she says. “The beatings came at 3 in the morning when you didn’t make your quota.”

At 18, Ampah got pregnant, and that’s when things started to turn around. She escaped her pimp, got back into school and became a medical assistant and then a licensed practical nurse, taking a giant step toward becoming independent.

Today, working at THRIVE is her passion. “I can empathize with [the patients], empower them, and let them know that this is just one moment in their lives that shouldn’t define them and that they can overcome it,” Ampah says.

As an outreach coordinator, she visits those streets where she once walked, going into dark alleys to share resources—and her story—with victims. She is street savvy enough to know how to avoid confrontations, fully aware that traffickers and pimps could be watching.

It should not have taken a Super Bowl coming to Miami to shine a spotlight on the problem, Ampah says. “We have Ultra, spring breaks, boat shows, a Memorial Day weekend celebration—human trafficking is here year-round,” she adds.

Not all of Potter’s battles have been fought advocating for and administering care to survivors. It has also been a fight for funding. While a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office for Victims of Crime supports some aspects of the clinic, grants do not cover everything—and they don’t last forever, leaving the clinic with the challenge of finding additional support to sustain services. So, donations have helped take up the slack.

THRIVE is being replicated in at least one other Florida county and in Atlanta, where Juhi Jain, M.D. ’15, currently in the second year of a pediatric hematology/oncology fellowship at Emory University’s Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, is working with a team of physicians to establish a health care and victim services model.

Five years ago, it was Jain who sowed the seeds for what would become THRIVE, when she applied for and received an Arsht Research on Ethics and Community Grant to educate health care professionals about human trafficking through educational seminars.

Potter says THRIVE is succeeding, noting the low recidivism rates among survivors who are treated there. “Our patients,” she says, “are successfully reengineering their lives.”